Code Name- Beatriz

Code Name- Beatriz Oil Apocalypse Collection

Oil Apocalypse Collection A Dawn of Mammals Collection

A Dawn of Mammals Collection Killer Pack (Dawn of Mammals Book 4)

Killer Pack (Dawn of Mammals Book 4) Bled Dry

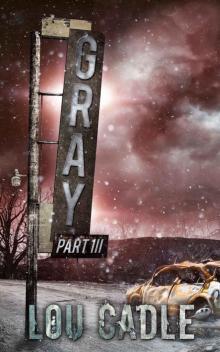

Bled Dry Gray (Book 1)

Gray (Book 1) Dawn of Mammals (Book 4): Killer Pack

Dawn of Mammals (Book 4): Killer Pack Bleeding (Oil Apocalypse Book 2)

Bleeding (Oil Apocalypse Book 2) Dawn of Mammals (Book 5): Mammoth

Dawn of Mammals (Book 5): Mammoth Saber Tooth (Dawn of Mammals Book 1)

Saber Tooth (Dawn of Mammals Book 1) Natural Disaster (Book 2): Quake

Natural Disaster (Book 2): Quake Hell Pig (Dawn of Mammals Book 3)

Hell Pig (Dawn of Mammals Book 3) Bled Dry (Oil Apocalypse Book 3)

Bled Dry (Oil Apocalypse Book 3) Desolated

Desolated Parched

Parched Natural Disaster (Book 3): Storm

Natural Disaster (Book 3): Storm Natural Disaster (Book 1): Erupt

Natural Disaster (Book 1): Erupt Slashed (Oil Apocalypse Book 1)

Slashed (Oil Apocalypse Book 1) Mammoth (Dawn of Mammals Book 5)

Mammoth (Dawn of Mammals Book 5) Gray (Book 3)

Gray (Book 3)